There’s a particular kind of intellectual vertigo that comes from agreeing with people you’re supposed to hate. I felt it recently re-reading

’s 2019 essay on cancel culture – written in the immediate aftermath of her own cancellation. I found myself nodding along to her critique of liberal authoritarianism, then remembering – oh right, this is the same person who now cherry-picks studies about puberty blockers, the same person who thinks trans kids are just confused tomboys.The discomfort is immediate, made especially sharp by my genuine admiration for so much of her work. As a trans person, watching a thinker I respect go down the gender-critical path creates a conflict far more personal than simple ideological opposition. It forces a very real question: should I now distrust everything she says? And, in even asking that, am I already self-censoring – already trapped in the very discourse prison she’s describing?

The trap operates like this: An idea makes perfect sense, but then a name attaches itself to the idea, and the whole thing feels contaminated. The internal monologue kicks in, a frantic self-audit – can I hold this truth, now that I know its source is tainted? If I agree with her on this, what does that make me? This spiral shows how deeply I’ve internalised the very discourse policing I claim to oppose.

The crushing irony is that this spiral – this psychological coercion – is exactly what Power describes in her 2019 essay. Her argument is that parts of the left, in a desperate bid to feel morally “good,” require an enemy. They must constantly manufacture a “bad other” – a figure who holds complicated or challenging views – precisely so those views can be dismissed without genuine engagement. My own impulse to recoil from her correct analysis simply proved her point.

This psychological reflex points to something more complicated than simple left dysfunction. Political discourse – across movements, not just “the left” – has increasingly focused on boundary maintenance over transformation. The pattern appears everywhere: environmental movements split between green capitalism and degrowth, racial justice efforts divide over reform versus abolition, labour struggles fracture between union negotiations and calls for worker ownership. In each case, it manifests as an obsession with drawing and policing the lines of discourse.

Then, it uncovers a deeper political crisis. While we’ve been busy becoming exquisite curators of our own ideological spaces, meticulously patrolling the borders of our in-groups, the foundational structures of the world around us remain largely unchallenged. The energy we spend debating who is allowed to speak is energy we don’t spend questioning the terms of the conversation itself. We end up fighting over the seating arrangements in a room whose walls are rapidly closing in.

This obsession, in turn, is animated by a collapse of vision – a retreat into a purely reformist imagination where one sees injustice and thinks: how do we fix this? How do we make the system more fair, more inclusive, more humane? In other words, a political project that admits the system will persist; we’re simply negotiating the terms of our incorporation.

What’s more is that the “reformist” versus “revolutionary” binary itself flattens how change actually happens. The Black Panthers ran breakfast programs while advocating revolution. ACT UP demanded immediate AIDS treatment while challenging fundamental assumptions about health and state responsibility. These both constituted rejections of the state’s terms. The breakfast program said: the state starves Black children. The AIDS activism said: the state murders through neglect. Both refused the legitimacy of the system they engaged.

Some of this stems from material conditions – social media rewards polarisation, precarity makes people defensive of hard-won spaces. But the deeper collapse is our inability to imagine anything beyond incorporation or exclusion. We’ve lost the capacity to think of destruction as a creative act.

Some of us are constitutionally incapable of this kind of thinking. We look at the same injustices and think: the entire foundation is rotten. We need to start over. We need new categories, new ways of being, new forms of life that transcend modifications of what already exists.

The impulse goes far beyond arguments over bathrooms. When I see debates about workplace inclusion, part of me engages with the necessity of protecting trans people from discrimination. Another part is screaming: why are we fighting for fairer inclusion in corporate structures that exploit us all anyway? Why are we demanding recognition from a state that requires us to fit into neat boxes to receive rights? Why settle for a place within the nuclear family instead of imagining new forms of kinship and care entirely?

Put simply, why are we fighting for inclusion in systems that shouldn't exist to begin with? Therein lies the difference. The reformist sees a door marked “wrong gender” and demands entry. Some of us want to burn down the whole building.

Policing the boundaries

This position – wanting transformation rather than reform – makes the current discourse around trans rights particularly unbearable. Over the past decade or so, we’ve watched two authoritarian camps come to life, each more interested in policing boundaries than pursuing liberation.

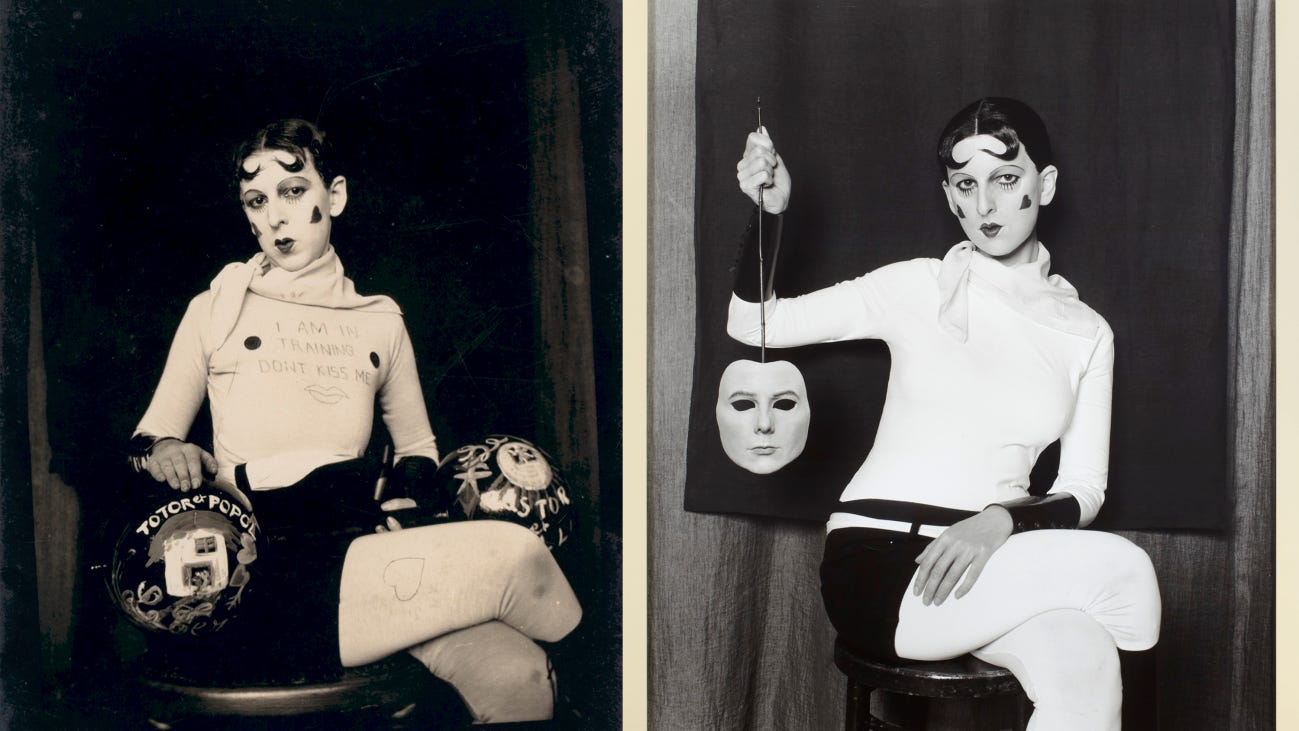

On one side, TERFs ally themselves with the religious right, weaponising feminist language to advance deeply conservative agendas. Alex Charnley and Michael Richmond chart this exact dynamic in their recent book, Fascism and the Women’s Cause. The trajectory of figures like Power provides a textbook example of the process they describe: they start with reasonable-sounding concerns about women’s rights, then slide into defending rigid gender roles and traditional masculinity.

Dominic Fox, reviewing Power’s What Do Men Want?, saw through this project immediately. He recognised that books like Power’s promise to tell you what you are – man or woman, with all the supposed natural desires that follow – and then insist:

“Since this is what you are... this is how you should rightly seek to realise yourself; if it appears that you are trying to realise some other kind of being than that which you are, then failure and misery are inevitable.”

This encapsulates the reactionary core of the TERF project – it insists we must want what our biology supposedly dictates. Its goal is to simply reduce the wild complexity of human sexed life to corral people into reproductive silos. This requires its own public relations, a set of myths about what men and women are really like, myths that tell us what we ought to want based on our sexed biology. It is, in short, a project of social control, the very opposite of liberation – a bewildering turn for a thinker of Power’s calibre.

The myths required to sustain this project are as old as they are simple: If you’re born male, you must want to be a protective patriarch. If you’re born female, you must embrace your nurturing nature. Anyone whose existence deviates from these scripts – what Fox, citing Robin Dembroff, calls “wilful gender deviance” – gets painted as warped, damaged, or a danger to others. The whole ideology demands conformity to roles that many of us find impossible to inhabit, all to maintain a rigid social order and strict division of reproductive labour.

On the other side of this divide, certain prominent voices and platforms within trans activism have embraced their own forms of boundary policing – quick to exclude, slow to engage with complexity. This isn’t to paint all trans activism with the same brush; many trans people and organisers work tirelessly on multiple fronts, combining immediate survival needs with long-term transformation. But there’s a visible strain, particularly in online spaces, that seems more invested in maintaining ideological purity than building the coalitions necessary for genuine change.

Power diagnoses this impulse not merely as a desire to “be good,” but as an existential fear of complexity. The act of cancellation, she argues, is a defence mechanism against a world that is too complicated, a way to restore a sense of order by force. She describes it as a childish regression:

“What does it mean to ‘cancel’ somebody, or to cancel an idea, or attempt to? It is to put one’s fingers in one’s ears, like a child overwhelmed by the world outside, and to scream ‘this person is bad! I am good! I don’t want to hear it! I am afraid!’”

This hits at something I’m sure many of us have experienced – watching people who claim to want liberation spend more energy policing each other’s thoughts than imagining new worlds. Every conversation becomes a potential contamination, every platform a sacred ground to be protected from “dangerous ideas.”

Yet we must also recognise why this defensive posture exists. Trans communities face genuine threats – legislative attacks, physical violence, systematic discrimination. In this context, what gets labelled “cancellation” often begins as community self-defence. The question becomes: when does necessary protection transform into counterproductive insularity?

This dynamic found its perfect, exhausting embodiment in the campaigns against Natalie Wynn, a leftist trans philosopher who releases video essays as ContraPoints. A prime example was the backlash to her 2019 video, “Opulence,” where she included a minor voiceover from Buck Angel – an older, controversial trans man known for views often perceived as hostile to non-binary identities. The actual content of Wynn’s video – a tour de force on class and aesthetics – was almost entirely ignored. The outrage fixated instead on the “sin” of association. Wynn was immediately accused of being a “truscum” – shorthand for a transmedicalist who believes one must have gender dysphoria to be legitimately trans. This single accusation reframed her as an enemy to non-binary people and cast her out of certain community spaces.

This case reveals the complexity Power describes, but also what she misses. Yes, Wynn’s response – a nuanced video essay about the nature of cancellation itself – only intensified some campaigns to isolate her. Yes, this demonstrated a belief that some ideas are too “dangerous” for people to hear. But it also reflected genuine hurt from non-binary people who’ve faced erasure and invalidation, including from other trans people. The tragedy was that legitimate concerns about inclusion got channelled into a dynamic that ultimately served no one’s liberation.

The crushing irony in a case like Wynn’s is the profound elitism of the position, exactly as Power points out. To justify the campaign, Wynn’s critics had to adopt a stance of absolute condescension toward their own audience. In the name of protecting the marginalised, they must first assume those they claim to protect are too simple-minded to handle a conflicting idea. As Power writes in 2019:

“Paradoxically, imagining that the other is too stupid to make up their own mind, that they must be kept away from ‘dangerous ideas’ in case they think for themselves, is the most elitist and hierarchical attitude there is. Yet this is what the cancellers – those who believe themselves to be on the side of equality! – think…”

And so the irony lands with its full weight. The logic presumed that other trans people – the viewers – had to be treated like children, shielded from a “problematic” voice lest they be contaminated. These self-appointed guardians fight for our right to exist within current systems, but they shut down any difficult conversation that might challenge how we think about those systems, or ourselves.

This refusal of difficulty traps us on a miserable battlefield, defined by a choice between two kinds of reaction. On one side is the conservative demand that we conform to a biological past; on the other, a liberal demand that we conform to a narrow political present. Between these positions – one denying our existence, the other constraining it within existing systems – the possibility of genuinely transformative futures gets lost. The question becomes: how do we protect our communities while maintaining the openness necessary for radical imagination?

The revolutionary act of becoming

That lost future is the radical potential of trans existence itself and its power to reveal our most cherished categories as political fictions. It is a future that requires a different kind of political imagination, one that steps away from the fight for inclusion in systems that are themselves the source of the problem.

This is the territory opened up by the philosopher Paul Preciado, who treats the body not as something to be corrected to fit a norm, but as the very site of a political uprising. His project becomes a search for an “exit” from the entire regime of sexual difference, foregoing pleas for inclusion. Such a project is necessarily hostile to both authoritarian poles: the conservative one that seeks to rigidly enforce the system, and the liberal one whose highest ambition is to win a sanctioned place inside of it. In choosing to “decolonise, disidentify, debinarify”1 himself, he demonstrates that gender is a system to be hacked and re-written. He writes that accepting the norm would have required the “destruction of my life force,”2 a cost far greater than any social penalty.

Yet Preciado’s radical vision, while intellectually liberating, exists alongside the material reality that most trans people navigate daily. Not everyone can afford to live as a philosophical experiment. For many, “inclusion” in existing systems – however flawed – means access to healthcare, employment, housing, and basic safety. The challenge isn’t choosing between Preciado’s radical refusal and pragmatic reform, but understanding how both operate simultaneously, how survival within current systems can coexist with imagining their dissolution.

What makes this coexistence possible is that the very act of trans existence – whether pursuing medical transition, legal recognition, or simply living authentically – already undermines the system it engages with. Each trans person navigating these institutions exposes their fundamental incoherence. This lived act of becoming reveals the central lie of the conservative gender project, the political sleight-of-hand that Dominic Fox identifies: the need to corral people into simple, reproductive roles. This project relies on a foundational deception, claiming that the statistical observation of two primary reproductive forms across the human species is the same thing as a rigid, biological law for every single person.

Fox wryly notes the TERF slogan “adult human female” actually contains its own refutation: one is not born an adult. We arrive in the world radically unready. What we call our “sex” is the result of a lifetime of development – an intricate process of biology, environment, and experience. The binary is a political project designed to freeze this process, to deny the messy, ongoing work of becoming.

The act of transition itself is the refutation. A person proves through their own life that a statistical pattern is not a personal destiny. They show the strict boxes of “male” and “female” that organise so much of our world – from bathrooms to pay scales to parental leave policies – for what they are: political choices, not natural laws.

This revolutionary potential is what truly terrifies the conservative camp, but it also deeply unsettles the liberal one. For the right, it threatens a perceived natural order. For the liberal reformist, the possibility of moving beyond asking “which bathroom can I use?” to asking “why do we organise space, labour, and desire around this binary at all?” is a major strategic disruption.

Every trans person forced to choose between two doors embodies this contradiction – their very need to choose exposes the system’s absurdity. This is how the radical possibility gets subsumed into frameworks offering only “acceptance” and “tolerance,” as if fitting more neatly into the gender binary was always the goal. We’re offered a seat at the table when the radical question reveals the table itself is the problem.

The way out

Herein lies the path out of the trap. The revolutionary potential of trans existence extends far beyond a single community, offering a lesson for any politics that seeks genuine liberation. By demonstrating that gender – a category so fundamental to our social order – is a political choice and a mutable code, trans people offer a key to dismantling other systems of control that rely on an appeal to a “natural” order: the family, the nation, the market. The frantic policing of gender boundaries from both camps reacts to the immediate presence of trans people and the deeper, terrifying possibility they represent: if gender can be unwound, anything can.

The tragedy is that so much of the left, the very political tradition that should champion this possibility, is unable to see it. This blindness is symptomatic of how the left has been colonised by liberal modes of thinking that are fundamentally anti-radical. We equate disagreement with violence; we mistake exclusion from discourse for liberation; we police each other’s associations more vigorously than we organise against actual systems of oppression. We’ve accepted the liberal framework that says politics is about managing existing arrangements instead of imagining new worlds.

In this way, we’ve already lost.

The challenge, then, is developing forms of political engagement that resist capture by either pole – that can work within existing conditions while maintaining sight of radical horizons. All of this makes me think about Rami Kaminski’s concept of the “otrovert” – someone who feels like an outsider in any group, who can maintain individual connections without needing to belong to the collective. There’s something here about the kind of thinking we desperately need: people who can engage with ideas from Nina Power and reformist trans activists without feeling compelled to join either tribe. Both sides aren’t equally valid – Power’s positions on trans youth cause real harm – but the very demand to choose sides forecloses the possibility of finding genuinely new ground.

The most disturbing part of Power’s trajectory is that her exclusion from left spaces has pushed her toward the only people still willing to platform her: the right. This is the cancel culture paradox in action. By refusing to engage with heterodox thinkers, we don’t eliminate their ideas – we risk ceding them to our enemies. The dynamic of Power's public exclusion from the left has, at the very least, accelerated her trajectory toward platforms on the right. A potential, if difficult, interlocutor now writes for audiences who want to eliminate trans people entirely.

Let me be absolutely clear: this isn’t an argument for some mythical “middle ground” between trans rights and transphobia. The problem is that the entire discourse has been captured by frameworks that make radical thought impossible. We’re handed a script where the only lines are inclusion or exclusion, acceptance or rejection. These terms guarantee our defeat.

What would refusing these terms entirely mean? Insisting on spaces where we can think dangerously, where we can engage with difficult ideas without immediately sorting them into “fascist” or “progressive” bins? Where we can acknowledge that someone like Power might be catastrophically wrong about trans kids while potentially right about cancel culture? Where we can dream of worlds beyond both liberal tolerance and conservative tradition?

The material reality is stark. Trans youth face increasing legislative attacks. Laws multiply daily. In this context, abstract theoretical discussions can feel like luxury. But I’d argue the opposite: without radical imagination, we’re stuck playing defence forever, begging for acceptance from systems that were never designed to include us. The choice extends beyond Power’s gender essentialism and liberal inclusion politics. We either accept the world as it is – with minor modifications – or dare to envision it completely transformed. This constitutes one of the rare binaries that we cannot escape.

Such a transformation won’t come from better discourse norms or more careful cancellations. We need thinkers willing to occupy impossible positions, to risk being misunderstood by everyone rather than understood by the wrong people for the wrong reasons. We need organisers who work on multiple timescales simultaneously – fighting for immediate survival while building toward unrecognisable futures. We need communities that can hold contradiction, that can protect their members while remaining porous enough for transformation. Theirs is the work of building these spaces amid intense political assault and shielding them from co-option – perhaps the most difficult strategic question we face. This text serves as a compass, pointing to that necessary horizon.

The future of gender liberation depends on refusing the current discourse war’s terms, on transcending trans-inclusive or gender-critical positions entirely. The question is whether we’re brave enough to imagine a world where those categories no longer exist – and strategic enough to build it while surviving this one.

Further reading

Nina Power, "Cancelled", (2019).

Nina Power, "Trans Barbarism", Compact Magazine.

Nina Power, "The Trans War on Tomboys", Compact Magazine.

Alex Charnley and Michael Richmond, Fascism and the Women’s Cause.

Dominic Fox, "Do Not Want", The Last Instance.

Nina Power, What Do Men Want?, (Penguin, 2022).

ContraPoints (Natalie Wynn), "Opulence".

ContraPoints (Natalie Wynn), "Canceling".

Paul B. Preciado, Can the Monster Speak?, trans. Frank Wynne (Fitzcarraldo Editions, 2021), p. 33

ibid., p. 34

Thx for this. It's something I've wrestled with in trying to work out my own politics. I find myself getting very frustrated by the people who insist revolution is the only path forward and anything less is being a sellout. But also understand the frustration of feeling like incrementalism dilutes and drowns actual change. It _is_ a fundamental tension that doesn't have an absolute resolution. And I think history tends to say that actual revolution is a) rare, b) bloody, and c) has as much chance of backfiring and making things worse as it does improving anything. Every Marxist revolution I can think of seems to have resulted in an authoritarian state, ultimately. But conversely: the conditions that sparked those revolutions were repressive and awful and deserved to be overthrown. I kind of hate it but am forced to conclude that slow, incremental, and perpetually insufficient progress is usually better. But as the essay says: "The challenge, then, is developing forms of political engagement that resist capture by either pole – that can work within existing conditions while maintaining sight of radical horizons."

The other issue brought up here is tribalism. I think it's hard to avoid that. And I think there is genuine danger in the seductive powers of disingenuous arguments, and looking at the speaker and not just the speech is an entirely legitimate way to assess motive and legitimacy. Feature not bug. Sure, you also have to resist the impulse to stay in echo chambers, but political actors (well-funded and platformed, usually) abusing the idea of the public square and good-faith debate to smuggle in propaganda is a much bigger problem. Refusing to rehash faux-arguments in favor of political talking points is a good thing that defends the utility and integrity of the public square; it's not a priori evidence that free thought and legitimate debate have been stifled.

I cannot applaud loudly enough in a purely text-based comment, but you can imagine it.

I am struck by how well this article examines many different aspects of binary this-or-that arguments about trans existence, and from them both distills a generalized pattern and observes that the pattern itself is the problem. That's not easy to do.

I arrived at a similar "radical thinker" position in an article I wrote a while back on the narrow question of trans women in sports (https://sonjamblack.substack.com/p/what-nobodys-asking-about-trans-women) and am more than a little jealous that I did not spot the generalization Freya has identified and articulated here.